By Louis J. Kern

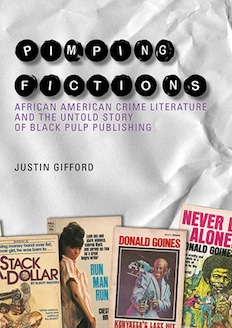

As a response to H. Bruce Franklin’s 1989 call for a scholarly study of popular African American fiction, Gifford here provides an insightful reading of black crime literature that has heretofore received virtually no critical attention. In scope the volume ranges from the detective fiction of Chester Himes and Iceberg Slim’s (Robert Beck) pimp fiction in the 1960s to its inversion by the female practitioners of the genre—Vickie Stringer, Sister Souljah, and Nikki Turner in the 1990s. Players (est. 1973), the black response to Playboy, developed as a spin-off by Holloway House, the white-owned publisher of black pulp fiction from 1965 through the 1980s, receives proper attention as an expression of the Life—the urban black subcultural world of the pimp, hustler, and con man.

Focusing on the racial history of the production of black crime literature, Gifford presents a dynamic understanding of mass-market black literature grounded in the immediate political, historical, racial, and gender circumstances of its production and distribution. His sources range from interviews with authors and publishers to book contracts, unpublished manuscripts, and letters.

Most of the works on review here were the product of prisoners or ex-cons for whom the figure of the pimp was central—an heroic figure, who, through exaggerated machismo, linguistic virtuousity, ritualized exploitative interaction, reproduction of free enterprise forms, and the performance of conspicuous consumption, mastered the environment of the mean streets. In Gifford’s reading, this figure is a flawed hero of working class black male fantasy. Through hustling, he seeks to escape the racial confines of segregated inner city projects and legal incarceration. He aspires to social mobility and suburban residency, but rejects the strategies of the black middle class. In the Kenyatta novels of Donald Goines the pimp becomes a revolutionary figure, seeking to reclaim the streets from the white power establishment. But ironically, all his efforts fail, rooted as they are on the exploitation of women; his efforts at personal and racial progress merely reproduce and transfer the disposition of human expendability. Later pimp tradition shifted to wish fulfillment in the Iceman novels of Joseph Nazel that envision successful black antiauthoritarian violence and escape from racially determined boundaries, and Players expanded the definition of pimp to the middle class, while the female street literature of the 1990s overturned the misogyny of earlier works—“the pimp game got flipped on . . . [its] ass.”

In close correlation with the racialist structure of American society, Gifford argues that the situation of black writers serving white pulp publishers was analogous to that of the fictionalized pimps; their work was appropriated by editors, confined by the commercial needs of publishers, and its revolutionary potential suppressed; they were the whores of marginal publishers. But attributing racial bias to Holloway House obscures the fact that all pulp publishers, exploited and defrauded their writers to the same extent and in the same ways.

Linking these works to hip hop, gangsta rap and blaxploitation films, this volume offers a compelling case for a reexamination of this neglected literature that comprises 50-70 percent of titles sold in black bookstores. With a readership estimated in the millions, these popular vehicles may well reach more readers than those of canonically-approved authors like Richard Wright, Toni Morrison, or Maya Angelou. As Gifford makes clear, anyone wishing to understand the modern black experience cannot afford to ignore the massive output and phenomenal popularity of black crime literature.

Louis J. Kern (ΦBK, Clark University,1965) is professor emeritus of history at Hofstra University. Hofstra University is home to the Omega of New York chapter of Phi Beta Kappa.