By Katy Sternberger

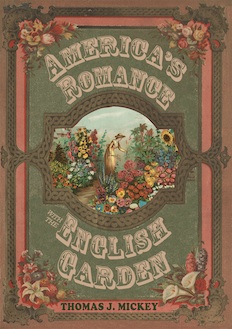

American gardeners have long been attracted to the ideals of English garden design; after all, England had a reputation for a “developed sense of horticulture.” What inspired, in part, this infatuation were mass-produced seed and nursery catalogs that portrayed the “quintessential English-style garden” and revolutionized the advertising business, as Thomas J. Mickey discusses in America’s Romance with the English Garden.

Upon receiving a fellowship from the Smithsonian Institution’s Horticultural Services Division, Mickey investigated America’s long-standing fascination with English gardening principles. He read nineteenth-century garden catalogs, which were produced by seed companies and nurseries in order to promote a particular style of gardening, generate business, and inspire consumers (especially women) to garden. These catalogs are archived at institutions including the National Museum of Natural History, the library at the Department of Agriculture, the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, and the Arnold Arboretum at Harvard University.

Mickey discovered that, through the use of mass-marketing techniques in the catalogs, American gardeners felt that the English garden was the look they had to achieve: well-manicured lawns, well-placed trees and shrubs, individual garden beds, and kitchen gardens. “This book tells the story of how the nineteenth-century seed and nursery industry sold the American gardener the English garden,” Mickey writes.

The book begins with an overview of the various styles that influenced American gardening over time, which began with Dutch geometric gardens in the early seventeenth century and colonial New England dooryard gardens in the eighteenth century. Early on, however, English gardens appealed to Americans, and English landscape design principles steadily grew in popularity through the nineteenth century with the Victorian garden. Indeed, “the English garden became the fashion,” Mickey explains. Americans traveled to view English gardens while British gardeners traveled to America to provide instruction, using examples from England’s extensive horticultural traditions. American gardeners wanted to imitate what they saw in British publications, such as William Robinson’s The Wild Garden or Thomas Meehan’s Gardener’s Monthly.

British seed companies and nurseries started sending their catalogs to America, and then American garden suppliers started producing their own catalogs, which became a very competitive business. Companies often catered to specific niches, such as kitchen gardens or flower gardens. While native plants were available for sale, gardeners preferred to collect exotic plants, “nature’s scattered excellencies.” In their catalogs, the nurseries also built their reputation in order to create a bond with consumers. Business at first was regional, but by the end of the nineteenth century was international, and “the catalog was the salesman.” Mickey goes on to explain in detail the content of the catalogs and how seed companies advertised themselves and their products.

As an example of the ways in which seed catalogs persuaded American gardeners, consider the lawn. During the second half of the nineteenth century, as people began settling in the suburbs and wanted to create home gardens instead of kitchen gardens, garden catalogs targeted the middle class. The idea of the lawn as an indication of social class arose after the Civil War, and the seed catalogs increasingly encouraged consumers to maintain a certain appearance about their homes. “The middle-class image was not just about gardening but about creating an identity through the arrangement of walkways, plants, and lawn, along with flowers and vegetables,” Mickey writes. Lawn replaced farmland, and since the lawn connected one house to the next, it established a sense of community. In fact, in 1884, the Vick Seed Company told readers of its catalog that they should grow gardens in order to increase their property values. Even today, the lawn remains a status symbol.

Mickey tells the stories of the personalities—the nurserymen, writers, and garden designers—who shaped the plant industry and the concept of advertising. Beautifully illustrated with archival images from seed catalogs and photographs from Mickey’s own garden, America’s Romance with the English Garden is well researched and a fascinating read for anyone interested in horticulture, history, and advertising and media.

Katy Sternberger (ΦBK, University of New Hampshire, 2012) is a writer, editor, and researcher. After graduating from the English/journalism program at the University of New Hampshire, she is now pursuing her master’s degree in archives management at Simmons College.